Women’s fashion at the turn of the century was constrictive, to put it mildly. In some cases, it was lethal.

In the opening scene of The Ghost in Her, the heroine, Maggie O’Connor, walks along a desolate back street with her sister Nessa, who is in child labor, and eyes an advertisement for corsets.

Excerpt

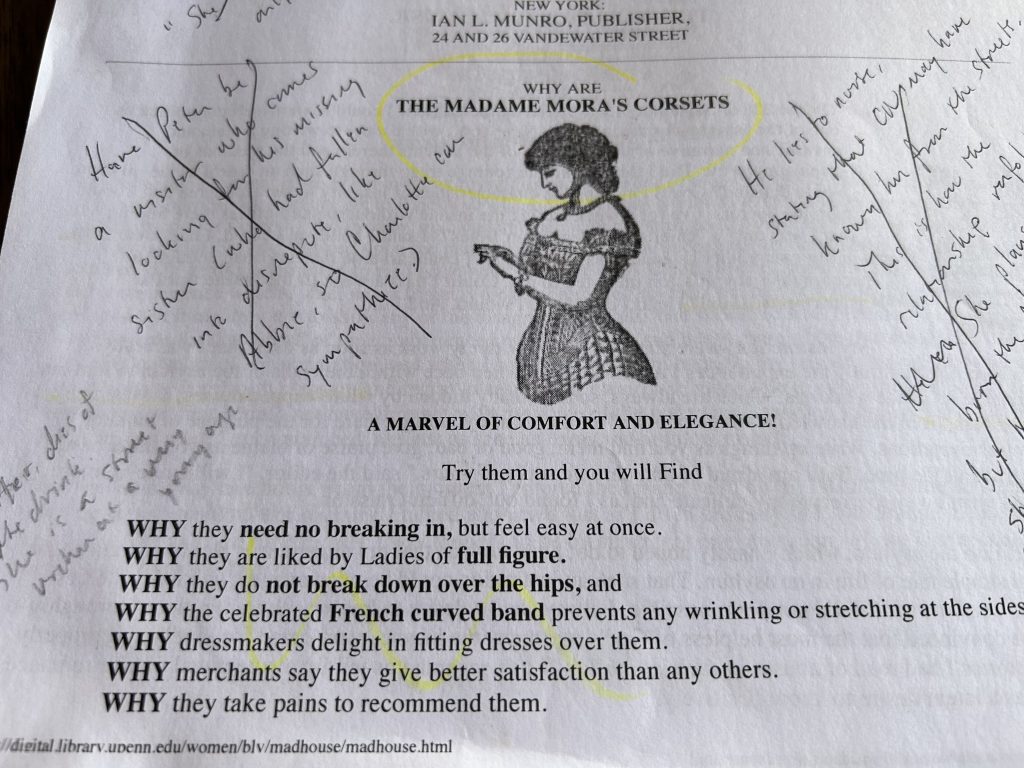

Nessa’s breathing grew labored—the long, desperate grunts giving way to staccato gasps. Looking for a distraction, I crossed the cobblestone path and read an advertisement on a neighboring doorway.

Madame Martha’s Magnificent Corsets.

A Marvel of Comfort and Elegance!

Beneath this proud proclamation was a detailed sketch of a full-bodied woman, cleavage bulging and hips bursting, with a nearly pencil-thin waist. Dressed in a fashionable gown, she admired a ring on her outstretched hand. Long rippling lines stretched from the stone, the artist’s amateur attempt at depicting its dazzling radiance.

“Tell me what it says,” Nessa weakly said.

I snickered and read: “The girdle this lady wears needs no breaking in. It’s as comfortable as a satin under-slip.”

“Impossible,” Nessa dryly remarked.

The inspiration for this scene came from an actual advertisement for corsets that I discovered in Nellie Bly’s groundbreaking story, Ten Days in a Madhouse, which exposed the inhumane conditions of the NYC Lunatic Asylum in the late 1800s.

Ignore my chicken-scratched notes. I read Ten Days in a Madhouse early in the creative process while working out the plot and character details using different names.

In the opening scene of The Ghost in Her, the advertisement for Madame Martha’s Corsets is intended to juxtapose the gritty reality of what Maggie and her sister Nessa were experiencing at that moment. Dressed in ragged clothing and battered old shoes, the thought of wearing a girdle that unnaturally slims a woman’s waist by crushing her innards is nothing short of absurd.

For me, corsets are a symbol of the suppression of women in the 1800s. In order to achieve an unnatural hourglass figure, women pulled the laces as tightly as possible, resulting in reduced lung capacity. In some cases, the corsets caused atrophied back and chest muscles, and the compression of internal organs. Imagine digesting a five-course meal at the famous Delmonico’s restaurant dressed in a lacy vice. Some autopsies even evidenced rib cage deformity due to long-term corset usage.

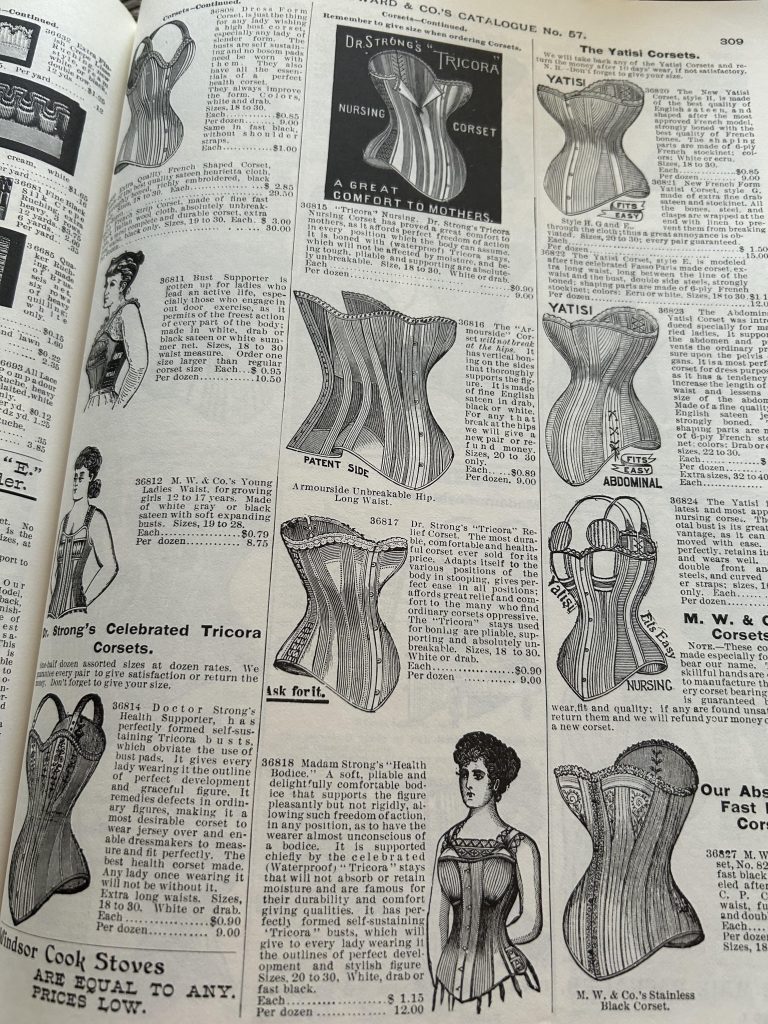

Desperate to maintain the illusion, many pregnant women wore special corsets designed to fit their expanding bellies. Here’s a photo, taken from The 1895 Edition of The Montgomery Ward Catalog depicting a corset that allowed the new mother, puffed up and exhausted, to maintain her figure while nursing her infant.

Women finally caught on to the dangers of being “tight-laced.” In 1873, author Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward wrote:

Burn up the corsets! … No, nor do you save the whalebones, you will never need whalebones again. Make a bonfire of the cruel steels that have lorded it over your thorax and abdomens for so many years and heave a sigh of relief, for your emancipation I assure you, from this moment has begun.

Something tells me that Ward would have also burned her bra if she lived in modern times. It all begs the age-old question, “How far should women go to achieve an appearance that is pleasing to men’s eyes?”

As for me, I’ll stick with sports bras and leggings, sans corsets. When faced with choosing comfort or image, I’ll pick comfort any day of the week. Evidently, the heroine of The Ghost in Her, Maggie O’Connor, agrees. The modest muslin dress she wears on the book cover allows her to walk with fluidity and grace whilst staring at fairies on a moonlit street.

Sources:

- https://www.geriwalton.com/death-by-corset-and-tight-lacings-in-the-1800s/

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2015/11/16/how-corsets-deformed-the-skeletons-of-victorian-women/?sh=4d785f7e799c

- https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/elizabeth-stuart-phelps-grandmother-bra-burners/

If you’re interested in learning more about Nellie Bly and her time on Blackwell’s Island, and you need a good laugh, check out this Drunk History Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7ZPl4FHyxc

“Burn up the corsets… from this moment has begun.”