We tend to think of tabloids as a modern-day phenomenon, beginning in the 1970s when housewives purchased them at supermarkets and returned home to read about Jackie Onassis’s latest scandal. In fact, The National Enquirer was first published in 1926, and cheap newspapers covering salacious crimes and celebrity gossip, also known as “penny papers,” first appeared in the 1830s.

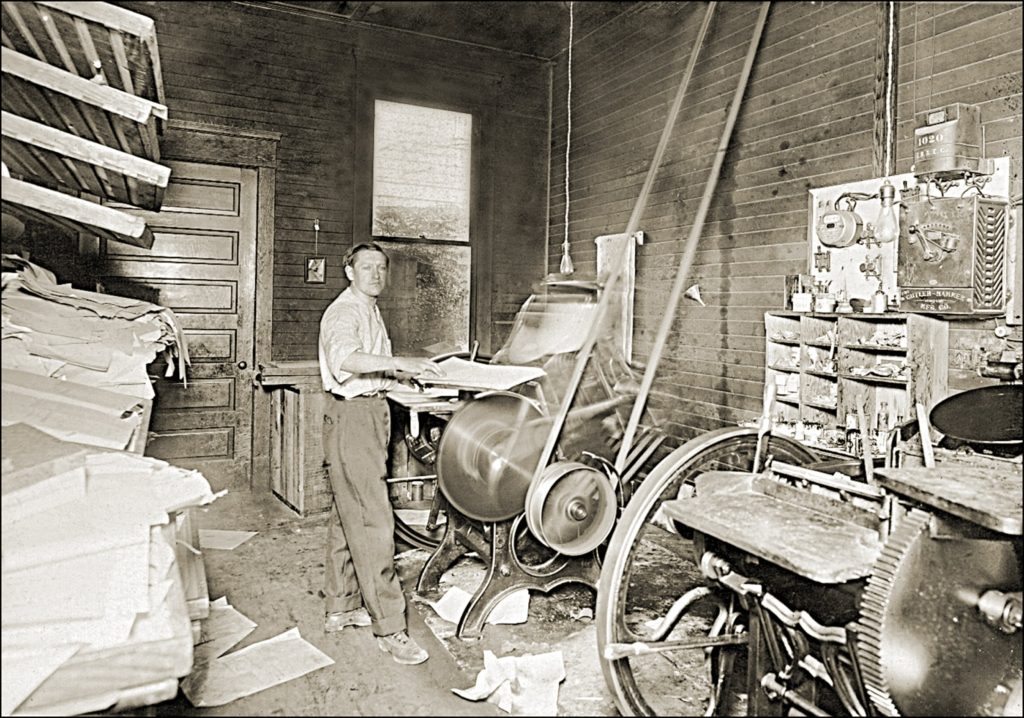

At the time, Western civilization was undergoing a communications revolution in which the advent of new technology- steam-driven printing presses and machine-made paper, enabled working-class readers to enjoy sensationalized articles comprising shorter sentences and paragraphs and simple vocabulary.

Woe to the woman who became the subject of public discourse, for the penny papers could devour her reputation faster than an energy vampire sucks the soul from his unsuspecting victim. In the first book of the Ungilded Series, The Ghost in Her, I describe the destitute Irish heroine, Maggie O’Connor, visiting the local library. Maggie references Flash, a tabloid that covers the titillating events of NYC’s Bowery District:

I walked to the west end of the room and entered the light-speckled treasure trove of weeklies and dailies that illustrated in words and etchings the activities of a city that never slept. So many vestiges of so many secret lives. The selection was enormous, ranging from the widely read New York Herald to street-smart, scandal-ridden dailies like Flash. In my fantasy world, I would be a Flash reporter. I was sure that I could describe the flamboyant happenings of the Bowery with more local color than a visiting writer on assignment.

Little does Maggie know that she will soon become Flash’s hottest damsel in distress. When Maggie is wrongfully committed to the NYC Lunatic Asylum, Flash gives her a new nickname, “Mad Maggie.” The derogatory moniker is intended to shape public opinion while erasing Maggie’s dignity, not unlike the tabloids that label Meghan Markle as, “The Difficult Duchess.”

When Maggie emerges triumphant and marries an architect who works for Andrew Carnegie, Flash dubs her “The Bowery Princess.” The title catches on, leading residents in the tenement district to proudly cheer for The Bowery Princess as Maggie and her groom throw candy to the crowds lining the Bowery streets on their wedding day:

“Don’t forget the candies!” Gershom shouted. I reached into the crate and tossed handfuls of hard candies and pennies over the crowd. People ran madly about, gathering the gifts.

“Thank you, Bowery Princess!” a little girl resembling wee Mary cried out. While the Flash reporter may have dubbed me the Bowery Princess with tongue firmly resting in cheek, the locales embraced the title with pride.

“Stop the carriage,” I told the driver. “You!” I called out, gesturing to the little girl.

Dumbstruck, she pointed her thumb to her chest.

“Yes, you, little love. Come here. I have a gift for you.”

She tripped across the roadway. I reached into the pocket of my tea gown and produced my mother’s roll-plate pin. She took hold of the pin, marveling at the enameled leaves.

She stared up at me, her eyes shining through the tears. “Thank you, Princess Maggie!”

“One day,” I replied, “you too will be a princess.” Seeing her wee face light up made the darkness that I experienced at the asylum miraculously melt away.

Whether the year is 1888, or 2023, media coverage can be a blessing or a curse. Fortunately for our heroine, Maggie O’Connor, the narrative turned in her favor!

Sources

Belonsky, Andrew, Sept. 8, 2018. “How the Penny Press Brought Great Journalism to Populist America” Daily Beast. https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-the-penny-press-brought-great-journalism-to-populist-america

Klein, Maury, 1996. “When New York Became the US Media Capital” https://www.city-journal.org/html/when-new-york-became-us-media-capital-11973.html